The Novel Coronavirus and the belief that it originated in the illegal wildlife trade, has highlighted this burning issue. Wildlife organisations have called for total bans on the trade; governments have made a range of announcements. But how effective have trade bans been in the past? And what are the market demands that sustain the trade? Can the steady supply be arrested at its source?

In this article, we investigate all these questions in the light of four dominant demands in the illegal wildlife trade:

- Traditional Medicine

- Bush Meat

- Exotic Pets

- Status Symbols

“The world has been confronted by wildlife crime for decades, but in recent years there has been a change in the scale and nature of this illicit activity. Wildlife crime has become a serious threat to the security, political stability, economy, natural resources and cultural heritage of many countries and regions. It threatens the survival of some of the world’s most charismatic, as well as many lesser-known species.”

– Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)

The Demand: Traditional Medicine

The Market

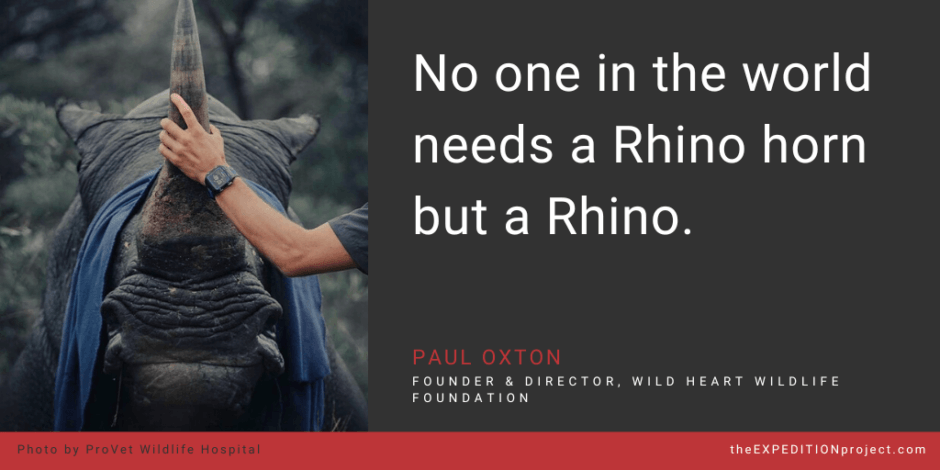

Rhino horn is in high demand in some Asian countries, where people use it for Traditional Chinese Medicine. Healers mix rhino horn with other natural ingredients to treat fever or relieve symptoms of arthritis and gout. Other historical uses include hallucinations, high blood pressure, typhoid, snakebite, food poisoning and even spiritual possession.

The Trade

CITES banned the international trade in rhino horn in 1977, but it still fetches huge profits illegally. At its peak, rhino horn was worth more than gold or cocaine, selling for up to $65,000 per kg. In recent years the price has dropped to close to $25,000 per kg. While this is good news, it may also cause new challenges as the horn becomes accessible to a wider customer base.

The Damage

The World Wildlife Fund reports that Asia and Africa were home to around 500,000 rhinos at the start of the 20th century. By 1970, their numbers had dwindled to just 70,000. Today, only about 27,000 rhinos remain in the wild.

South Africa’s Kruger National Park is home to the biggest rhino population. Unfortunately, this is also where the most poaching incidents occur. Out of 594 rhinos killed across the country in 2019, 327 were killed in the park.

When the demand for horns shot up after 2000, it sparked unprecedented rhino poaching in South Africa. Annual losses passed the 1,000 mark by 2012 and soared to 1,215 two years later. The figure did not fall below 1,000 until 2018 when 769 rhinos were lost to poachers.

Conservation Efforts

In July 2020, the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries disclosed that the country had lost 166 rhinos to poachers in the first six months of the year. This was a notable improvement in the first half of 2019 when 316 were killed.

“A decline in poaching for five consecutive years is a reflection of the diligent work of the men and women who put their lives on the line daily to combat rhino poaching, often coming into direct contact with ruthless poachers,” Minister Barbara Creecy said.

But, not everyone is excited about this news. From 2013 to 2019, South Africa lost at least 6,500 rhinos to poachers. That’s almost a quarter of the world’s rhino population. The government has not released rhino population statistics since the 2017 census. Their rationale is that the information is too sensitive and that releasing it could compromise anti-poaching efforts.

Without the data, it’s impossible to tell the proportion of rhinos poached each year, as a percentage of the remaining population. It may well be that the numbers are down because there are fewer rhinos left to poach.

The Demand: Bush Meat

The Market

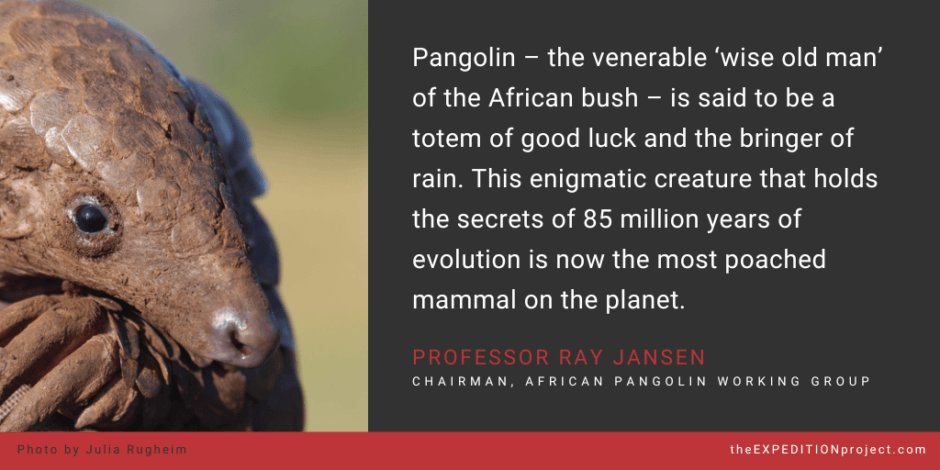

Pangolin meat is considered a delicacy in western and central Africa, as well as Vietnam and China. While the bush meat trade is not the primary threat to pangolins, its African supply chains have been enlisted to feed the never-ending Asian demand for their scales.

The Trade

CITES banned the international trade in the four Asian pangolin species in 2000. In 2017, the 183 countries that are party to the CITES treaty unanimously voted for a ban on commercial trade in all eight species. And yet, these shy anteaters are still the most trafficked mammals in the world. China recently banned the trade of pangolins within the country. This may help stop or at least slow down the global trade.

The Damage

Because pangolins live such secluded lives, researchers have not been able to estimate how many are left in the wild. Conservationists estimate that poachers remove up to 200,000 pangolins from the wild every year. The IUCN recently changed the classification of two out of the four African species from ‘Vulnerable’ to ‘Endangered’.

When threatened, pangolins curl into a ball and lay still, with their scales shielding them against even a lion’s bite. It is the only protection these shy, voiceless creatures have. Sadly, this incredible defence is the pangolin’s downfall when faced with its biggest threat: poachers. Remaining curled up makes it easy for a poacher to carry and hide.

“Last year, authorities intercepted more than 97 tons of scales from Africa representing over 150 000 animals. But the real poaching onslaught is far higher – only 10% of the illicit trade is intercepted,” says Professor Ray Jansen, chairman of the African Pangolin Working Group.

Conservation Efforts

Professor Ray Jansen, chairperson of the African Pangolin Working Group, has studied how traditional healers use these animals culturally, medicinally and zoologically.

“In some South African tribal societies, the pangolin is revered,” he says. He stresses that conservation efforts need to educate traditional healers on the implications of the unsustainable harvesting of wild pangolins. But there is no concept of extinction in African traditional belief systems, and this can make conservation efforts difficult, he says.

It may be more effective to focus on the potential threat posed to cultural belief systems if the animals are no longer available. In this way, the community can be mobilised as custodians of the pangolin, but their very cultural heritage.

To address the illegal wildlife trade, APWG is also targeting young people. “We have various educational programs more recently focusing on the rural youth via their schools,” Jansen reported. “We have partnered with multiple organisations that have existing networks and educational programs within these schools and have started a pangolin comic book campaign to bring the plight of pangolins to the people on the grassroots level throughout sub-Saharan Africa.”

The Demand: Exotic Pets

The Market

The magnificent cheetah’s grace and astounding speed have made it a status symbol, especially among young, wealthy people in the Gulf States. Social media glamourises exotic pets and this fuels the demand for live cheetahs, especially cubs.

The Trade

All international trade in wild-caught cheetah cubs violates CITES and is illegal. Nonetheless, there is evidence that enough cheetahs have been traded into the Gulf States over the past 20 years to impact wild populations. Experts believe that the illegal wildlife trade is a key driver of the decline in the Horn of Africa’s cheetah population.

A cub is worth between $200 and $300 in Somaliland. Prices vary greatly though: an unhealthy cub sells for as little as $80, but an older, healthy cub can cost up to $1,000. The same cheetah can fetch up to $15,000 in the Gulf States.

The Damage

The IUCN’s Red List classifies cheetahs as vulnerable, with fewer than 7,000 adults and adolescents left in the wild.

Smugglers exploit the political instability in the Horn of Africa to traffic cheetah cubs to the Middle East. Poachers and opportunistic nomads usually seize cubs when their mother hides them to go hunting. Most are only two to eight weeks old. They suffer abuse and starvation at the hands of poachers and dealers, added to the difficult trip across the Gulf of Aden. Sadly, up to 70 per cent die on the way to their buyers.

Conservation Efforts

The good news is that in January 2017, the United Arab Emirates set harsh penalties for owning or trading cheetahs and other big cats. Consequences include fines of up to $136,000 and up to six months of jail time. However, in spite of the tough stance on the illegal wildlife trade, the underground trade persists. Investigations have recorded more than 50 social media accounts within the UAE selling cheetah cubs.

With the help of regional partners and at the request of local governments, the Cheetah Conservation Fund enables confiscations whenever possible. In Somaliland, the organisation works with the Ministry of Environment and Rural Development to rescue cubs. Early in October, CFF reported a total of 29 rescues since January 2020. Despite dedicated care from CCF’s veterinary team at their Cheetah Safe House, three have died.

“The health and prosperity of people and of wild species are tied together. For animals like the cheetah to thrive, the human populations that live alongside them must be healthy and strong, with ample resources to sustain them”, says Dr. Laurie Marker, zoologist and CFF founder.

The Demand: Status Symbols

The Market

“Ivory is a status symbol,” says Cheryl Lo, wildlife crime manager for WWF-Hong Kong. “It’s a luxury product that people use to flaunt their wealth”, she explains. Ivory represents a complex aspect of the illegal wildlife trade.

In the Asian ivory markets that remain open (either legally or due to lack of enforcement), about 90 per cent of the customers hail from China. They can no longer buy the “white gold” in their home country, but stock is readily available just across national borders. They don’t regard it risky to carry small amounts of ivory back to China, even though it is illegal to do so without a permit.

The Trade

Poachers decimated the elephant population in the 70s and 80s. As a result, CITES issued a global ban on the ivory trade in 1989. Mainland China – where most of the demand originates – only followed suit in 2017. It took spirited public campaigns to achieve the same in Hong Kong. In 2018, its lawmakers finally voted to ban the trade and phase it out by 2021. But it’s still legal in Japan and other parts of Asia.

After the CITES ban, ivory prices plummeted and markets around the world stopped trading. Yet that was just the early effect of the ban. A new study shows that, underground, the price skyrocketed. In 2002, the price of ivory was about $100 per kilogram. By 2010, it hit $1,800 per kilogramme. But in another four years, it would peak at $2,100. The price has been slowly dropping since then, with the 2017 value said to have been $730 per kilogramme.

The Damage

Between 2007 and 2014, 30 per cent of Africa’s elephants were lost to poachers. Today, only 350,000 remain. At this rate of decline, half the remaining population will be gone by 2023. “Each year we are losing nearly 30,000 elephants,” says Dr Mike Chase, founder and director of Elephants without Borders. Poaching is now responsible for an 8% drop in the world’s total elephant population every year.

Although South Africa’s elephant population is stable, poaching is still a problem. In 2019, the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries reported that poachers killed 31 elephants. “This is a decrease in the number of elephants poached in 2018 when 71 were killed for their tusks,” it said in a statement. This is in stark contrast to countries in West and Central Africa, where local populations are in grave danger of extinction thanks to the illegal wildlife trade.

Conservation Efforts

“We have to address demand if we are ever going to truly tackle the poaching of elephants for ivory,” says Naomi Doak, head of conservation programs at The Royal Foundation, which leads United For Wildlife.

Past efforts have focused on raising awareness of the problem, urging people and companies not to buy or sell ivory, and making people aware of the Chinese ban. In 2016, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) took a different approach. The organisation teamed up with a psychosocial researcher to uncover what drives the desire to buy ivory. Insight into the cultural and social roots of that desire would enable WWF to counter them effectively. In the following year, they partnered with TRAFFIC (a wildlife trade monitoring network) and GlobeScan (a consumer research firm) to study the ivory use patterns of more than 2,000 people across 15 Chinese cities.

One example of the results relates to diehard buyers—those who had previously purchased ivory and who were likely to continue doing so despite the ban. These were more likely to be women in smaller cities, with medium-to-high incomes. The study showed that ivory attracts these women for a number of reasons: It is rare and beautiful, it carries cultural and spiritual significance, and it makes a good gift.

Since the study clarifies what motivates people to buy ivory, WWF can craft messages to reach them in effectively. “For millennials and female buyers, for example, emphasizing the ‘elephant welfare’ aspect seems to hit home,” says Caroline Prince, a WWF wildlife conservation program officer who worked on the study.

Ending the Illegal Wildlife Trade

The question that remains unanswered is whether the steady supply of stolen wildlife can be arrested at its source in the African bush. We understand what drives the demand. What drives the supply?

Simply put: poverty. A lack of awareness may be a contributing factor, but this is relatively easy to remedy with effective education. Addressing the pervasive need that drives people to poach is far harder to do. Ironically, though poaching may seem like a way out, it creates even bigger problems in the long run:

“Wildlife trafficking can destroy the natural resources on which national economies and livelihoods depend. It undermines conservation efforts, as well as efforts to eliminate poverty and to develop sustainable economic opportunities for rural communities.”

– Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)

Many South African reserves do invest in the surrounding communities and involve them in the trade that reserves generate. But Covid-19 has all but annihilated the tourism revenue these reserves depend on, putting conservation and communities on a knife edge. If you would like a novel way to contribute to this cause, have a look at our new Conservation in Action courses here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.